This is a brief summary of paper for me to study and organize it, What do you learn from context? Probing for sentence structure in contextualized word representations (Tenney et al., ICLR 2019) that I read and studied.

They investigated the abilities of syntactic and semnatic phenomena on contextualized embedding so introduce a suite of ‘edge probing’ tasks designed to probe the sub-sentence structure of contextualized embedding.

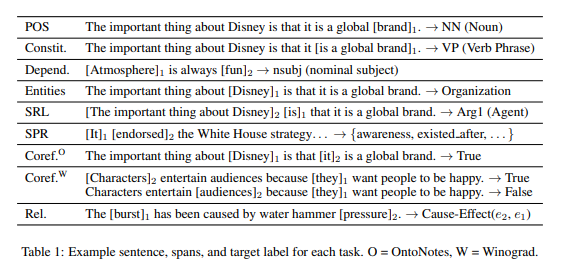

For the tasks which go through the abilities related to syntactic and semantic phenomena on contexturalized representation, those is :

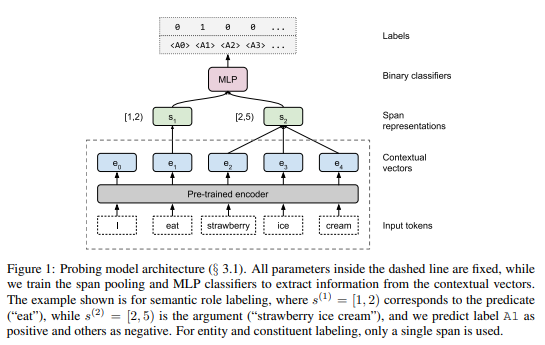

for sub-sentence structure, they designed probing model architecture as follows:

For probing contextualized representation, they represent a sentence as a list of tokens \(T\) = [\(t_0, t_1, …, t_n \)], and a lebeled edge as {\(s_1, s_2, L\)} where \(s_1\) = \([i^{(1)}, j^{(1)})\) and \(s_2\) = \([i^{(2)}, j^{(2)})\) as end-exclusive spans and \(L\) is label.

For unary edges such as constituent labels, \(s_2\) is omitted.

To focus on what information can be extracted from the contextualized representation. they take a list of contextural vectors \([e_1, e_2, e_3, …, e_n]\) and integar spans \(S_1\) = \([i^{(1)}, j^{(1)})\) and \(S_2\) = \([i^{(2)}, j^{(2)})\) as inputs, used a projection layer followed by the self-attention pooling operator of Lee et al. (2017)

As you can see figure above, they compared with four contextualized representation such as CoVe (McCann et al., 2017), ELMo (Peters et al., 2018), OpenAI GPT (Radford et al., 2018), and BERT (Devlin et al., 2018).

In addtion to four contextualized representations, they use Lexical baseline, randomized ELMo and Word-Level CNN as baseline to analyze What types of linguistic information (e.g. local context and long-rang context) is captured.

Specifically, their “edge probing” tasks is implemented as follows:

Part-of-speech tagging (POS) is the syntactic task of assigning tags such as noun, verb, adjective, etc. to individual tokens. They let \(s_1 \)= [i, i + 1) be a single token, and seek to predict the POS tag.

Constituent labeling is the more general task concerned with assigning a non-terminal label for a span of tokens within the phrase-structure parse of the sentence: e.g. is the span a noun phrase, a verb phrase, etc. They let \(s_1\) = [i, j) be a known constituent, and seek to predict the constituent label.

Dependency labeling is similar to constituent labeling, except that rather than aiming to position a span of tokens within the phrase structure, dependency labeling seeks to predict the functional relationships of one token relative to another: e.g. is in a modifier-head relationship, a subjectobject relationship, etc. They take \(s_1\) = [i, i + 1) to be a single token and \(s_2\) = [j, j + 1) to be its syntactic head, and seek to predict the dependency relation between tokens i and j.

Named entity labeling is the task of predicting the category of an entity referred to by a given span, e.g. does the entity refer to a person, a location, an organization, etc. They let \(s_1\) = [i, j) represent an entity span and seek to predict the entity type.

Semantic role labeling (SRL) is the task of imposing predicate-argument structure onto a natural language sentence: e.g. given a sentence like “Mary pushed John”, SRL is concerned with identifying “Mary” as the pusher and “John” as the pushee. They let \(s_1\) = \([i_1, j_1)\) represent a known predicate and \(s_2\) = \([i_2, j_2)\) represent a known argument of that predicate, and seek to predict the role that the argument s2 fills–e.g. ARG0 (agent, the pusher) vs. ARG1 (patient, the pushee).

Coreference is the task of determining whether two spans of tokens (“mentions”) refer to the same entity (or event): e.g. in a given context, do “Obama” and “the former president” refer to the same person, or do “New York City” and “there” refer to the same place. They let \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) represent known mentions, and seek to make a binary prediction of whether they co-refer.

Semantic proto-role (SPR) labeling is the task of annotating fine-grained, non-exclusive semantic attributes, such as change of state or awareness, over predicate-argument pairs. E.g. given the sentence “Mary pushed John”, whereas SRL is concerned with identifying “Mary” as the pusher, SPR is concerned with identifying attributes such as awareness (whether the pusher is aware that they are doing the pushing). They let \(s_1\) represent a predicate span and \(s_2\) a known argument head, and perform a multi-label classification over potential attributes of the predicateargument relation.

Relation Classification (Rel.) is the task of predicting the real-world relation that holds between two entities, typically given an inventory of symbolic relation types (often from an ontology or database schema). For example, given a sentence like “Mary is walking to work”, relation classification is concerned with linking “Mary” to “work” via the Entity-Destination relation. They let \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) represent known mentions, and seek to predict the relation type.

with probing model architecture, they use these tasks to explore how contextual embeddings improve on their lexical (context-independent) baselines.

They focus on four recent models for contextualized word embeddings–CoVe, ELMo, OpenAI GPT, and BERT.

Based on their analysis, they find evidence suggesting the following trends.

First, in general, contextualized embeddings improve over their non-contextualized counterparts largely on syntactic tasks (e.g. constituent labeling) in comparison to semantic tasks (e.g. coreference), suggesting that these embeddings encode syntax more so than higher-level semantics.

Second, the performance of ELMo cannot be fully explained by a model with access to local context, suggesting that the contextualized representations do encode distant linguistic information, which can help disambiguate longer-range dependency relations and higher-level syntactic structures.

For detailed experiment analysis, you can found in What do you learn from context? Probing for sentence structure in contextualized word representations (Tenney et al., arXiv 2019)

Reference

- Paper

- How to use html for alert